Trading places: Patrick McGee's "Apple in China"

And the capturing of the world's greatest company.

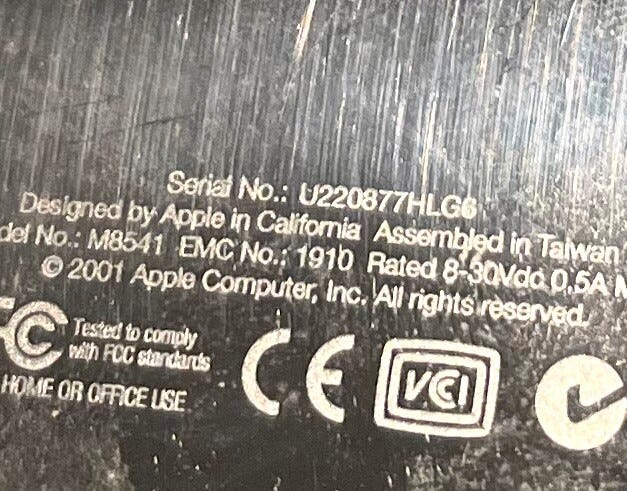

I’m not a collector. I Marie-Kondo the hell out of everything, probably because I live in a small Hong Kong flat. It’s odd, therefore, that I have kept my iPod from 2001. It stands atop a bookshelf among family photos.

This was the device that made Apple a cultural phenomenon. I was on my fifth year in Asia and constantly on the road. The Walkman had been iconic in the 1980s but was a pain for travelers: I was juggling cassette tapes that I had to pick or mix in advance. The iPod was “one thousand songs in your pocket”.

What a change! It was the sort of thing that made everyone optimistic about tech, Silicon Valley, digitalization, the whole shebang. I remember boarding the bus from Incheon Airport to get into town: another business traveler was also listing to his iPod. We had a friendly chat about the awesome little device. It’s hard to imagine an excited conversation between strangers over a new piece of tech today.

My iPod is etched, “Designed by Apple in California. Assembled in Taiwan.” This attests to the final days of Taiwan as a serious manufacturing hub for electronics. Although Apple would continue to rely on Taiwanese manufacturers such as Foxconn, they and it would soon move to mainland China.

In the early 1990s, while at grad school, I began to study the geopolitics of technology and big business. I was an avid free trader. The argument for outsourcing and offshoring went like this: the highest-value jobs remained in the US: pre-assembly, software design and corporate strategy; post-assembly, marketing and distribution. The assembly and putting-together of things was about low wages and low skills, and not the sort of work an American wanted to do.

This is in fact true for most businesses, including in tech. PCs running on Microsoft software are commoditized products that fit this pattern; so too peripherals, and even chips. “Designed in California and assembled in China” would seem like more of the same.

But Apple’s tagline on its products is deceptive. In Apple’s case, most of the truly high-value work was actually being done in China, by Taiwanese or mainland Chinese engineers in tandem with Apple teams. The work going on inside Foxconn and other campuses wasn’t just assembly. And Apple wasn’t merely offshoring production or outsourcing jobs. It was creating a new, unique model of globalization, often without being conscious of its actions – and this sleepwalking led it to become wholly dependent on China and its politics.

Financial Times journalist Patrick McGee has brought this story to life in his book, “Apple in China: The Capture of the World’s Greatest Company”.

His sources appear to be almost all from Apple. The research is meticulous, with many scenes built from hundreds of cross-referenced interviews. Tim Cook didn’t grant an interview, but I doubt he would have added any insight that McGee hadn’t dug up. It’s a strength that McGee notes he didn’t tell Apple’s PR teams about what he was up to.

The research’s weakness is that McGee has only limited insight into Terry Guo, the boss of Foxconn, and his associates or peers at other contractors. This is a story told from the American perspective. I don’t sense McGee had any input from Foxconn managers or people at mainland suppliers. Nonetheless this story is also about China – specifically the Chinafication of the global electronics industry.

McGee’s big question, the bee in his bonnet that kickstarted his research, was to explain how Apple manufactures its products. He found that Apple’s manufacturing strategy led it, willy-nilly, to train the Chinese workforce – not its Chinese workforce, but THE Chinese workforce, up to 28 million people by the company’s own estimate. Gradually Beijing forced Apple into shifting this effort away from commercially minded Taiwanese and Japanese contractors to local companies with a different objective: the ‘red supply chain’.

McGee traces the history of contract manufacturing in the US, which Steve Jobs resisted. Famous for his obsession with detail, Jobs wanted to control the making of his products. Apple couldn’t compete on price with PCs so it made a play for amazing design. This led to the elevation of figures like Jony Ives, who dreamed up machines that proved incredibly difficult to produce in a lab, let alone on a massive scale.

To realize these dreamy designs, the company partnered with companies like LG, which were willing to accept poor commercial terms in return for the prestigious business. From the start, these partner companies lacked the ability to meet Apple specs, so the company sent its engineers to both train and co-design solutions. The work with LG on the first iMacs set a template that would be repeated across the region.

“Apple is single-handedly responsible for bringing quality into Southeast Asia,” a former executive tells McGee. “If you look at the capability they brought up in that region, from a manufacturing standpoint, it’s solely on their presence and their demands on these organizations that caused them to build that competency.”

This scenario went nuclear when Foxconn, responding to Apple’s frustration at rising labor costs in the rest of Asia, brought them into China. Not only was labor still cheap there, but the local governments were eager to give away free land, free electricity, and build the peripheral infrastructure for contractors that promised lots of jobs in the export sector.

Lots of Western companies were outsourcing to China, but Apple’s motivation was different. As McGee puts it, Western PC companies were shifting to China because of what was available; Apple shifted because of what was possible. That meant turning armies of manual laborers into automatons that could assemble extremely complex products – in fact, the making of Apple products were increasingly impossible to automate.

They became instead highly bespoke, high-end, hand-made luxury goods – but built at scale. All because of highly trained, flexible, and essentially bonded labor in China, their lives controlled by the Party’s hukou system, with the solutions to tricky engineering challenges figured out on the ground between contractors and Apple engineers.

Guo, meanwhile, realized he could accept cutthroat margins or even loss-making business from Apple because his teams stood to learn knowledge that would be otherwise impossible to come by. This is what made Foxconn special among Apple’s many suppliers. But the same ethos gradually seeped further down layers of that chain; Foxconn and the like didn’t have the capacity to make every last item, be it glassware or circuitry or wireless connectivity. They in turn had to train up their sub-contractors (including future tech giants like BYD).

Although Apple took pains to retain its IP and its equipment, inevitably some of these companies were able to provide highly specialized services to other clients. Initially there were no other clients to trouble Apple – but then Huawei came along, followed by Xiaomi and Oppo.

This wasn’t just about Apple seeding its own competition. McGee recalls a prescient comment by Andy Grove, the former boss of Intel: “our pursuit of our individual businesses, which often involves transferring manufacturing and a great deal of engineering out of the country, has hindered our ability to bring innovations to scale at home. Without scaling, we don’t just lost jobs – we lose our hold on new technologies.”

Apple wasn’t the only one sleepwalking toward dependency on China: so were US politicians, who saw no need to regulate the tech industry. On the contrary, China’s joining the World Trade Organization in 2001 was believed by most people in Washington to be the catalyst to China’s eventual embrace of rule of law and liberal values.

Apple, meanwhile, was pouring people and resources into China, to solve one problem at a time. “We just got pulled in,” recollects one senior exec to McGee. “I was always like, ‘We’re gonna get exposed. This is too much China exposure.’”

To whatever extent his misgivings were voiced, no one in Cupertino seemed to care, or to appreciate the risk. Apple had a tighter grip than ever on its suppliers, who were jumping hoops to win and keep the business, and its products were becoming iconic best-sellers.

The first inkling that Apple did not have things under control came on the ground, as it was opening its first Apple Stores in Beijing and Shanghai. The iPhone was as big a hit in China as it was elsewhere, but it caught Apple by surprise.

McGee notes that the iPhone became the ultimate status symbol, which he says explains the surging demand, which quickly became hijacked by scalpers organized by crime gangs.

When I mentioned this passage of the book to my wife, she said right away, this was because gadgets were for gifts. China’s economy was growing at double digits and everyone needed a way to curry favor with politicians, party members, company bosses, clients – everyone. It’s notable that McGee’s account never cites this need: it’s just about status for the new middle class. That Apple executives never mentioned the role of gifts to McGee shows that the company’s people are still out of touch with China, despite its vital role as both a manufacturing site and a consumer market.

Back to the story: the company was never able to control the mafia-tinged waves of consumer demand and outrage when people wanted to hand in fake or improperly acquired phones. The Communist Party stoked tensions to bring Apple to heel. At first Tim Cook, then Jobs’s COO, and his people dismissed such troubles, but they misread the shifting sands.

Jobs’s attention lay elsewhere. He realized that the iPhone could be copied – and if it were copied by a telecom company, Apple would be sidelined. The company raced to develop the iPhone, with its full-touch-screen novelty. This was a co-creation with its Chinese suppliers, and the point at which ‘designed in California and assembled in China’ no longer rang true. Jony Ive’s department was designing just the user’s physical experience of a product, but everything else was being figured out on the ground.

Chinese people began to bristle at the idea that they were merely low-end assemblers, but Apple’s culture of secrecy perpetuated this commonly held view. Apple didn’t want competitors understanding how it operated in China, and it was better that the US public didn’t understand it either.

The ascension of Xi Jinping led to more than just grumbles among the Chinese: now the government was taking direct aim at Apple. It resented what it saw as a foreign company that had no joint ventures and no contracts (formal or otherwise) for technology transfer. Indeed, Apple had become the world’s largest manufacturer without owning any factories. But it was now totally dependent on clusters of contractors in China with a mix of skills, government subsidies, and docile workers that didn’t exist anywhere else.

Cook traveled to Beijing to reveal the extent of Apple’s investment in training, design, and equipment at all levels of the supply chain. The Chinese government relented – and began pushing Apple to use domestic suppliers instead of the Taiwanese. Apple soon found itself having to meet one demand after another, each of which shattered its stated tenets: ignoring local labor situations, adhering to anti-privacy data laws, undertaking local joint ventures, building up local companies whose mission is to uphold the principles of the Communist Party.

Despite these concessions, Apple now faces real competition from Huawei for top-tier retail customers. Cupertino was stunned by the quality of Huawei’s line of smartphones; after Trump’s first administration attacked Huawei and nearly killed the company, it has since come back stronger than ever.

One facet that doesn’t make McGee’s book is Xiaomi’s move into electric vehicles. Just as Steve Jobs recognized that the iPod would force Apple to develop the iPhone, Xiaomi has seen the shift that EVs were just iPhones on wheels. Indeed, Tesla followed an Apple-like strategy by building a gigafactory in Shanghai. But it’s the Chinese EV companies that have the scale and the supply chain to dominate this new industry.

At one point, Apple did consider developing its own line of EVs. I don’t know why it abandoned the idea, but my best guess is that the decision wasn’t about analyzing consumer demand in the West – it is that Apple’s own suppliers like BYD and its local competitors like Xiaomi already had the supply chain and the know-how to pull this off, at scale. Andy Grove’s warning has come back to haunt Cupertino. Chinese suppliers have all the skills now, not Apple engineers. There’s no need for electric cars to be ‘designed in California’.

Apple is still a behemoth. McGee notes that the company’s turn to services, and the way it interlinks its various products and the lock it has on many of the world’s most affluent consumers, ensures it has a future. But a future of diminishing returns, if the Xiaomi EV business ever turns profitable. And with Trump back in the White House, insulting world leaders left and right, plenty more of the well-heeled outside of the US will be tempted to try out a Huawei Mate instead of an iPhone.

Meanwhile, Apple remains leashed to the red supply chain, with attempts to diversify to India a day late and a dollar short. This leaves Apple in the crosshairs of US-China tensions, and therefore at the mercy of the temperament of two emperors.

“Apple in China” is not about China per se but it does illuminate how the country’s policies, sometimes deliberately, drew in and trapped major corporations and their IP. Less obviously it’s about the intense drive and hunger among Chinese entrepreneurs and workers that prepared them to toil under Apple’s yoke as well as drink deeply from Apple’s tree of knowledge – this is a story that’s even more ‘made in China’ than is reflected in McGee’s account.

Apple’s story is unique in the extent to which the company seemed to buck the Party’s playbook by going its own way, only to end up hopelessly entangled in Beijing’s web. To those of us who value global trade and connectivity, this has its upsides, and it hasn’t stopped Apple from becoming rich. But the company is no longer a bold innovator.

Patrick McGee has done fine work in bringing to light – and to life – the people and the decisions that made Apple both the world’s most successful company while costing it the one thing Steve Jobs valued the most: control.

“Apple in China: The Capture of the World’s Greatest Company”, by Patrick McGee; Scribner, New York: 2025.